A preferred return, often called the “pref,” is a common feature of how LPs potentially receive their contributed capital back in real estate investments. That return of capital is colloquially referred to as the “distribution waterfall.”

For investors, the pref can be one of the trickier concepts to interpret. Not all prefs are calculated the same way, and they are often confused with preferred equity, which is a separate concept in the capital stack.

This piece walks through the different types of prefs, provides examples, and clarifies how they differ from a preferred equity position.

What Is a Preferred Return?

A preferred return is a profit distribution preference. It dictates that profits — from operations, a sale, or a refinance — are paid to one class of equity before another until a specific return on initial investment is reached.

The pref is usually expressed as a percentage (for example, an 8 percent cumulative return), though it can also be structured as an equity multiple. The practical effect is simple: it subordinates the sponsor’s profits participation (the promote) until investors receive their agreed-upon return threshold. However, keep in mind, returns of any kind are never guaranteed.

For more on how a promote works, see What Does “Sponsor Promote” Mean in Real Estate Private Equity?

Preferred Return vs. Preferred Equity

A preferred return is not the same as preferred equity. The preferred return is a preference in the return on capital. Preferred equity is a repayment priority in the return of capital.

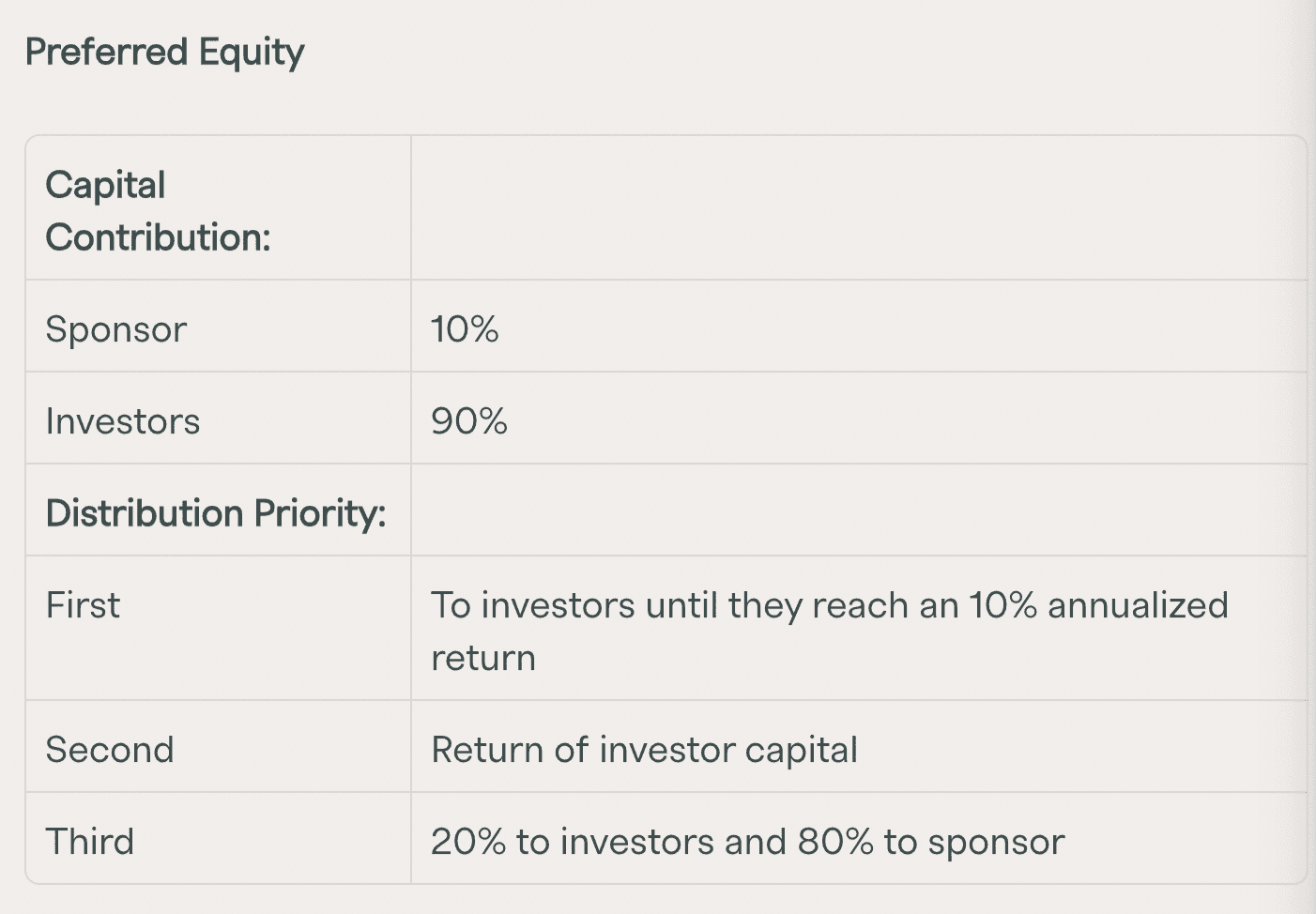

In a traditional preferred equity position, investors receive (1) their entire capital back, and (2) a set of preferred return, before subordinate common of JV equity receives any distributions.

If an investor does not receive its capital back before the sponsor or another equity tranche, that investor is not in a preferred equity position. The investor is a common or JV equity participant.

True vs. Pari Passu Preferred Returns

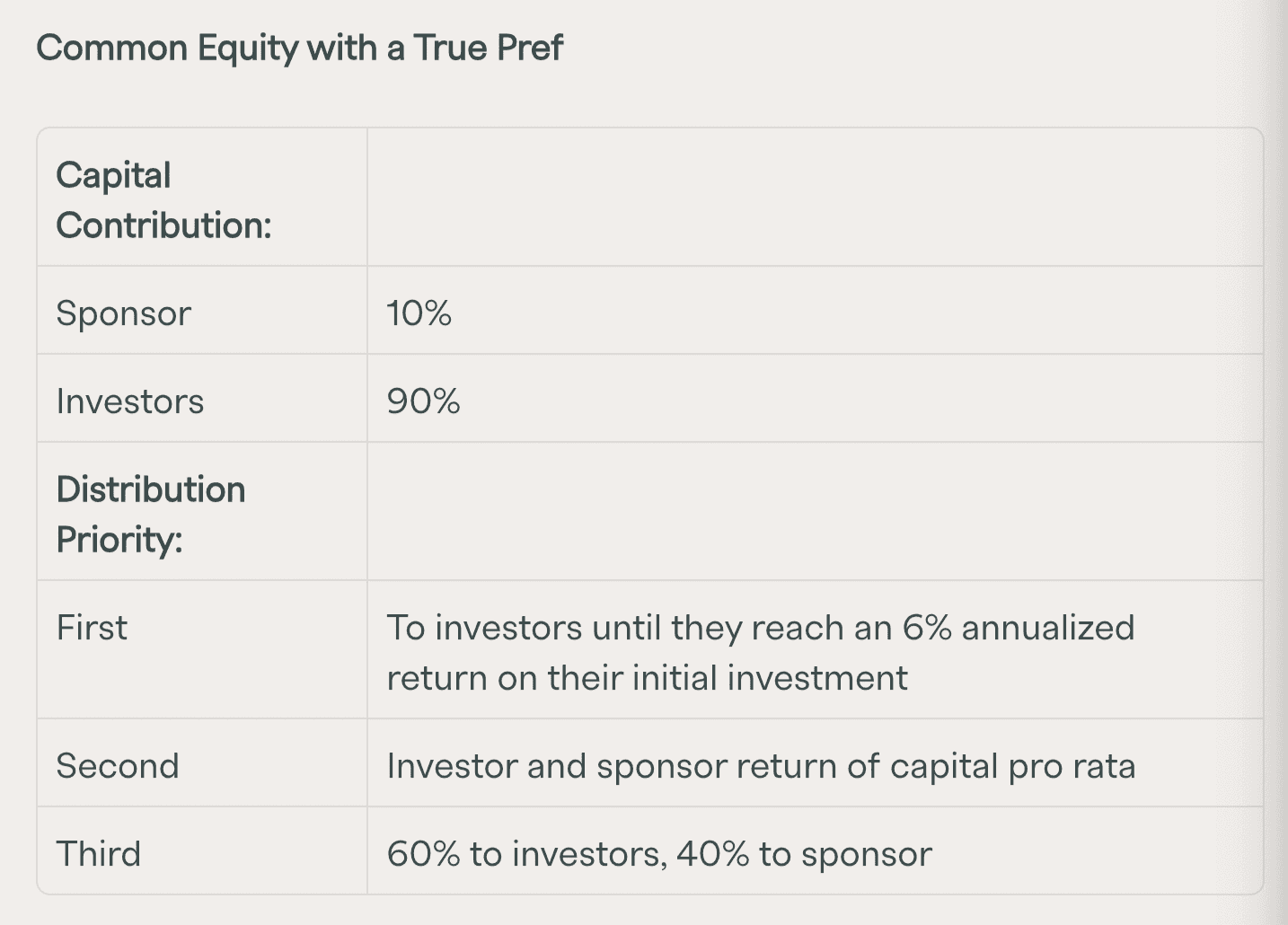

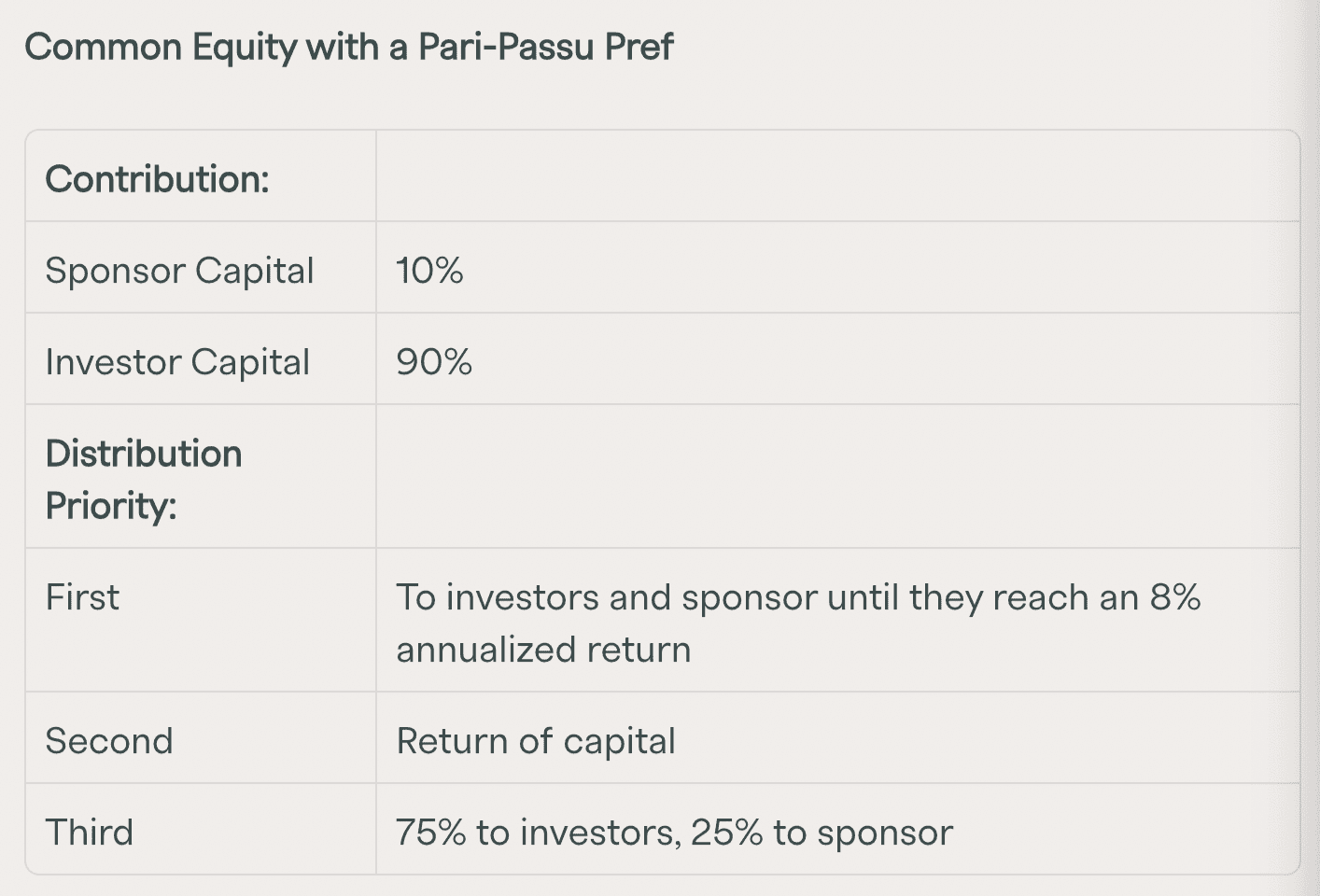

Common equity investors can still receive a pref, and the structure depends on how the sponsor’s own capital (the co-invest) is treated. A true preferred return pays the investor first. The sponsor does not receive profits until the investor’s pref is fully met. A pari passu preferred return pays the investor and sponsor the same pref at the same time.

With a true pref, investor capital receives priority treatment. With a pari-passu pref, investor and sponsor capital are treated identically until the pref is satisfied. The sponsor only earns disproportionate upside once the promote kicks in.

To help clarify these concepts, consider the following examples. These returns are for illustration only.

Explanation: Investors receive their capital back and a ten percent annualized return before the sponsor receives anything. After that, the sponsor receives its capital. All remaining profits are split 20 percent to investors / 80 percent to sponsor.

This structure gives investors a true preferred return, but limits their potential upside compared to a JV equity position.

Explanation: Investors receive a six percent true pref before the sponsor receives any distributions. After that pref, capital is returned pro rata. Excess profits split 60 percent to investors and 40 percent to the sponsor.

Because this is a true pref — meaning investors get paid first — the pref rate is typically lower than in a pari-passu structure.

Explanation: Both investor and sponsor capital receive the eight percent pref at the same time and receive their capital back pro rata. Above the eight percent hurdle, excess profits split 75 percent to investors / 25 percent to sponsor, with the sponsor earning disproportionate upside through the promote.

Investors do not receive priority over the sponsor in this structure. Their repayment risk is higher relative to a true pref, but they share in more of the potential upside.

Simple vs. Cumulative (Compounding) Preferred Returns

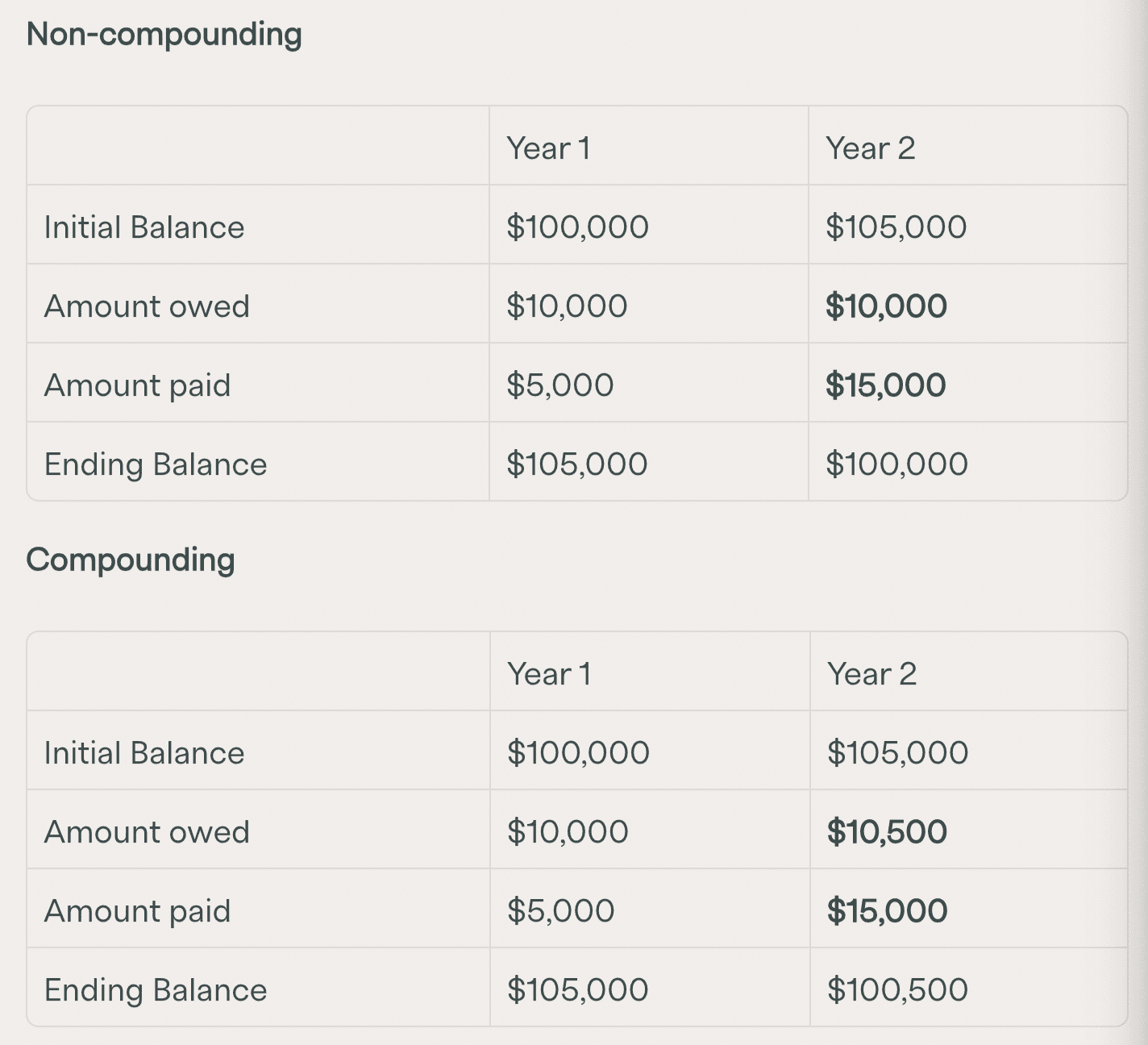

Prefs are not always calculated using the same method. They can be either simple interest or compounding. With simple interest, unpaid pref accrues but does not compound. With compounding interest, unpaid pref is added to the capital balance and compounds into future pref calculations.

As an example, imagine an investor is entitled to a ten percent annual pref. In year one, only five percent is paid. In year two, the cash flow allows for a 15 percent payment.

This chart is for illustrative purposes only.

Because of compounding, the investor still accrues an additional $500 owed going into Year 3. Over multiple years, a compounded pref can grow meaningfully when earlier periods have distribution shortfalls.

Crowd Street requires sponsors to clearly disclose how their preferred return is structured, including whether it is true or pari passu, simple or compounding. Investors can find these details on each offering’s Summary of Terms page and should review the pref mechanics carefully before committing capital.