Waterfall structures in commercial real estate investing can be complex. One element that often leads to confusion is how the sponsor’s (General Partner (GP) co-investment) is structured relative to Limited Partner (LP) capital.

It’s easy for LPs to misinterpret cash-flow splits and profit allocations because profits in CRE partnerships can be divided in several ways. But while the mechanics may differ, the economic outcome can often be very similar. Understanding the three most common organizational structures — and how cash flows move through each — helps investors get clearer on GP vs. LP returns.

This article outlines those structures and walks through how cash distributions typically work. All examples are purely hypothetical and for illustrative purposes only.

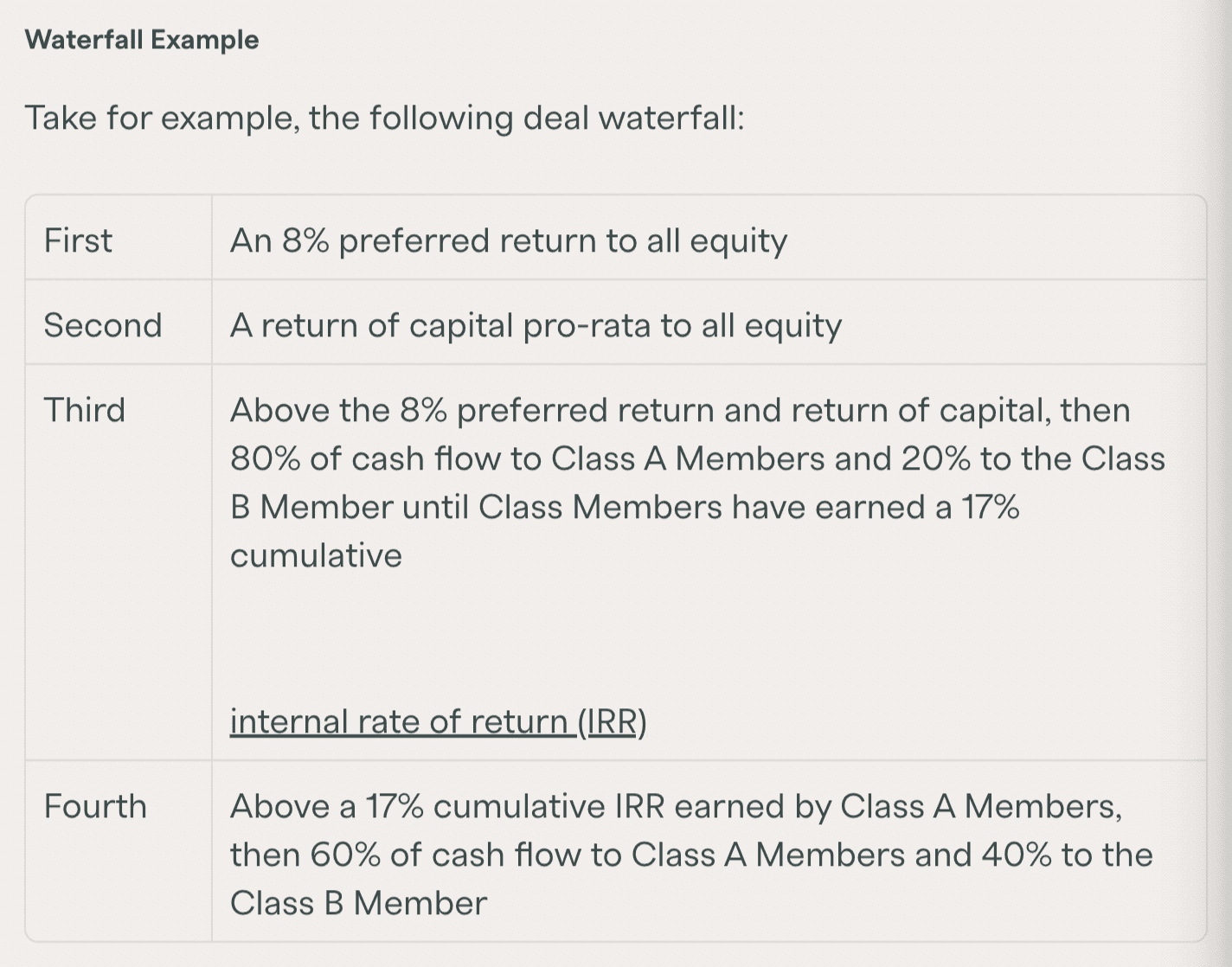

Structure One: The Single LLC

Generally considered, the simplest structure is one in which the GP forms a single LLC (a Special Purpose Entity or “SPE”) and contributes all equity, including GP co-investment, into that entity. From an organizational standpoint, the GP and all LPs sit together as Class A Members.

To receive a promote, the sponsor usually forms a separate Class B Member entity (commonly with a nominal capitalization, such as $100). This Class B member exists solely to receive potential promote distributions once the performance hurdles are met.

Because the sponsor’s co-investment sits alongside LP equity in the same class, this structure makes it straightforward for investors to track how cash flows split between GP and LP. It also cleanly separates (promote) distributions (paid to the Class B Member) from the sponsor’s pro-rata share as a Class A co-investor.

This structure generally delivers profit splits “as advertised,” since the sponsor’s co-investment is part of Class A. But not all deals follow this approach, which can make apples-to-apples comparisons more difficult for investors.

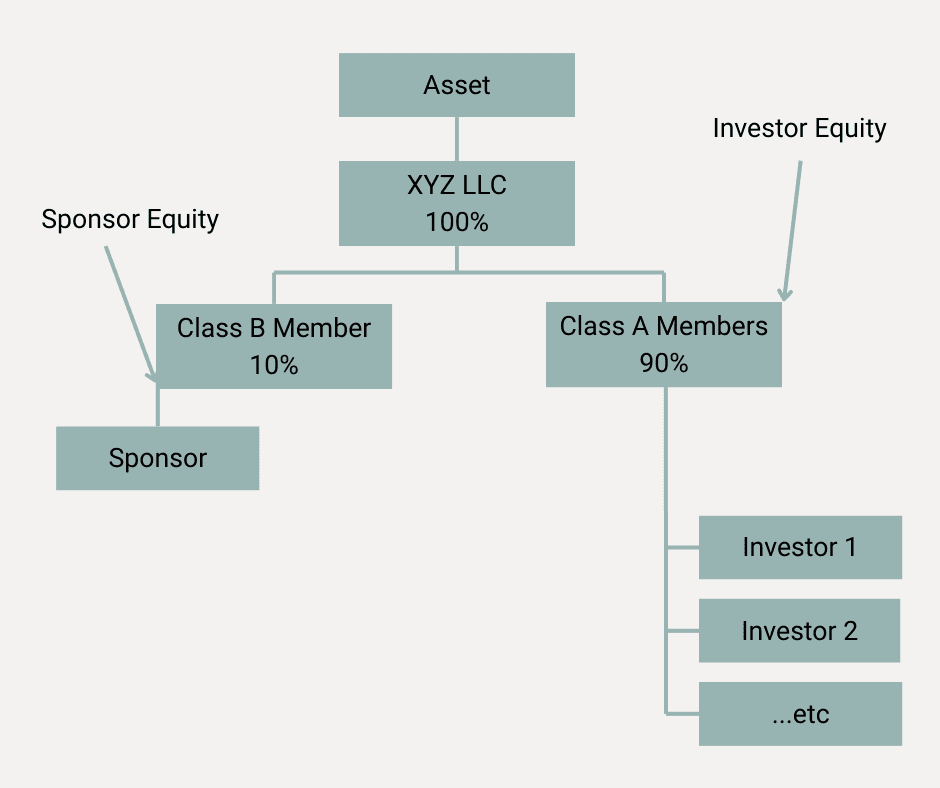

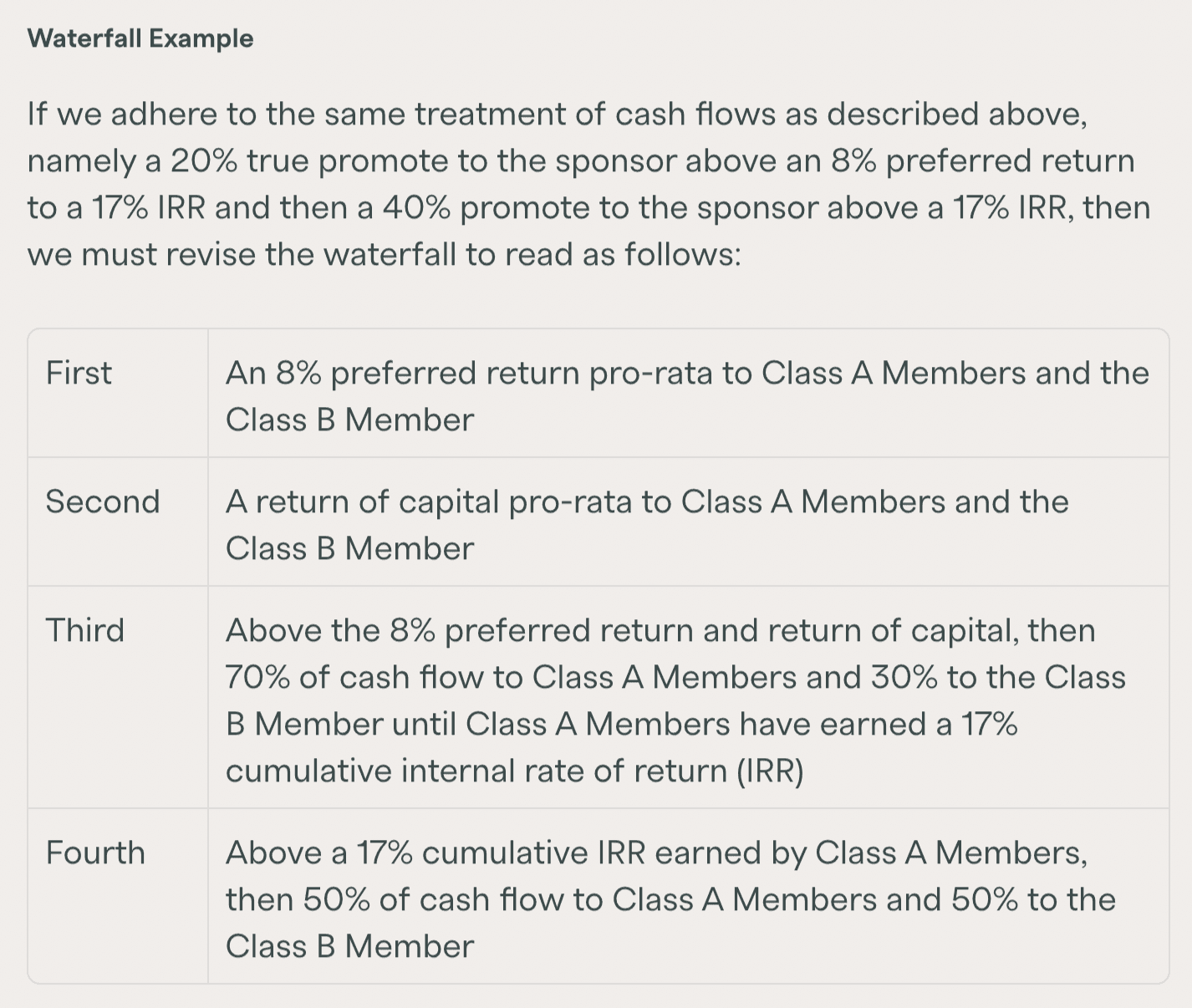

Structure Two: Sponsor Contribution as Class B Member

In some deals, the sponsor contributes its co-investment directly into the Class B Member instead of joining LPs in the Class A class. In this setup, generally 90 percent of capital comes from Class A Members (LPs) and ten percent comes from the Class B Member (sponsor), but the treatment of the two classes differs.

Because the sponsor’s capital is not contributed as Class A equity, the term “all equity” no longer applies. Waterfall language must reflect the separate treatment of each class.

In this waterfall structure, two differences stand out. First, a portion of the preferred return and return of capital must go to the Class B Member because it is a co-investor. Second, the splits to the Class B Member increase to reflect that the first ten percent of post-pref cash flow represents its pro-rata equity share — the promote only begins above that level. This is why the splits shift to 30 percent and 50 percent.

The key takeaway is that these are cash-flow splits, not pure promote splits. You only isolate the promote after accounting for the Class B Member’s ten percent co-investment. This can easily lead investors to assume the promote is larger than it is. Control provisions for both Class A and Class B Members sit within a single LLC Agreement — still one entity with two share classes.

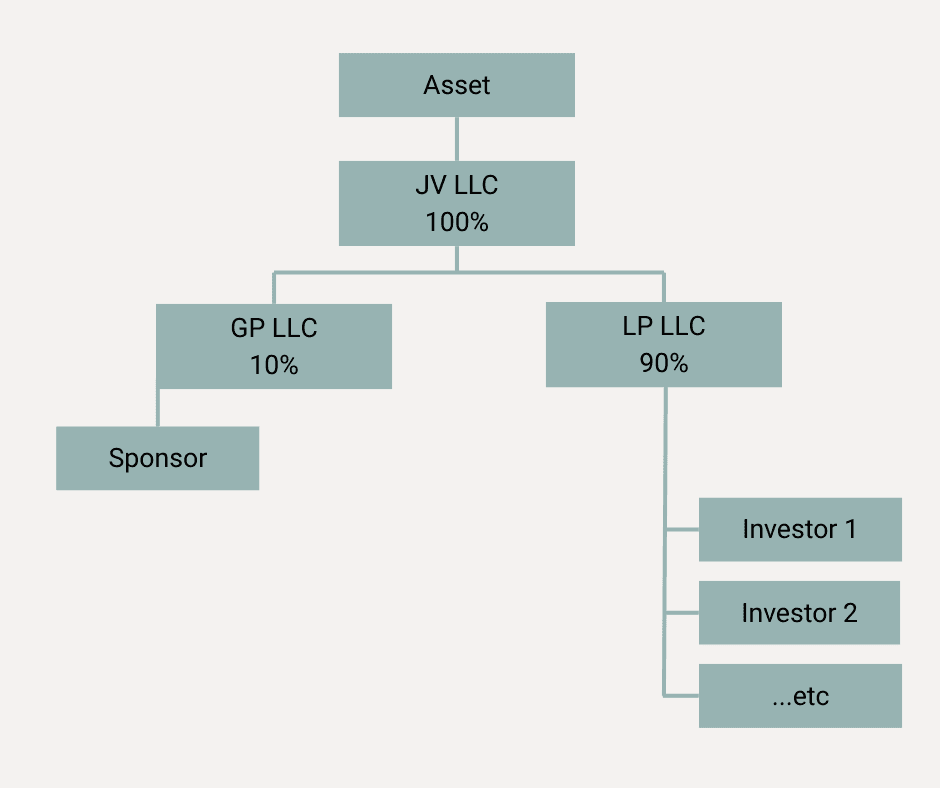

Structure Three: The JV LLC

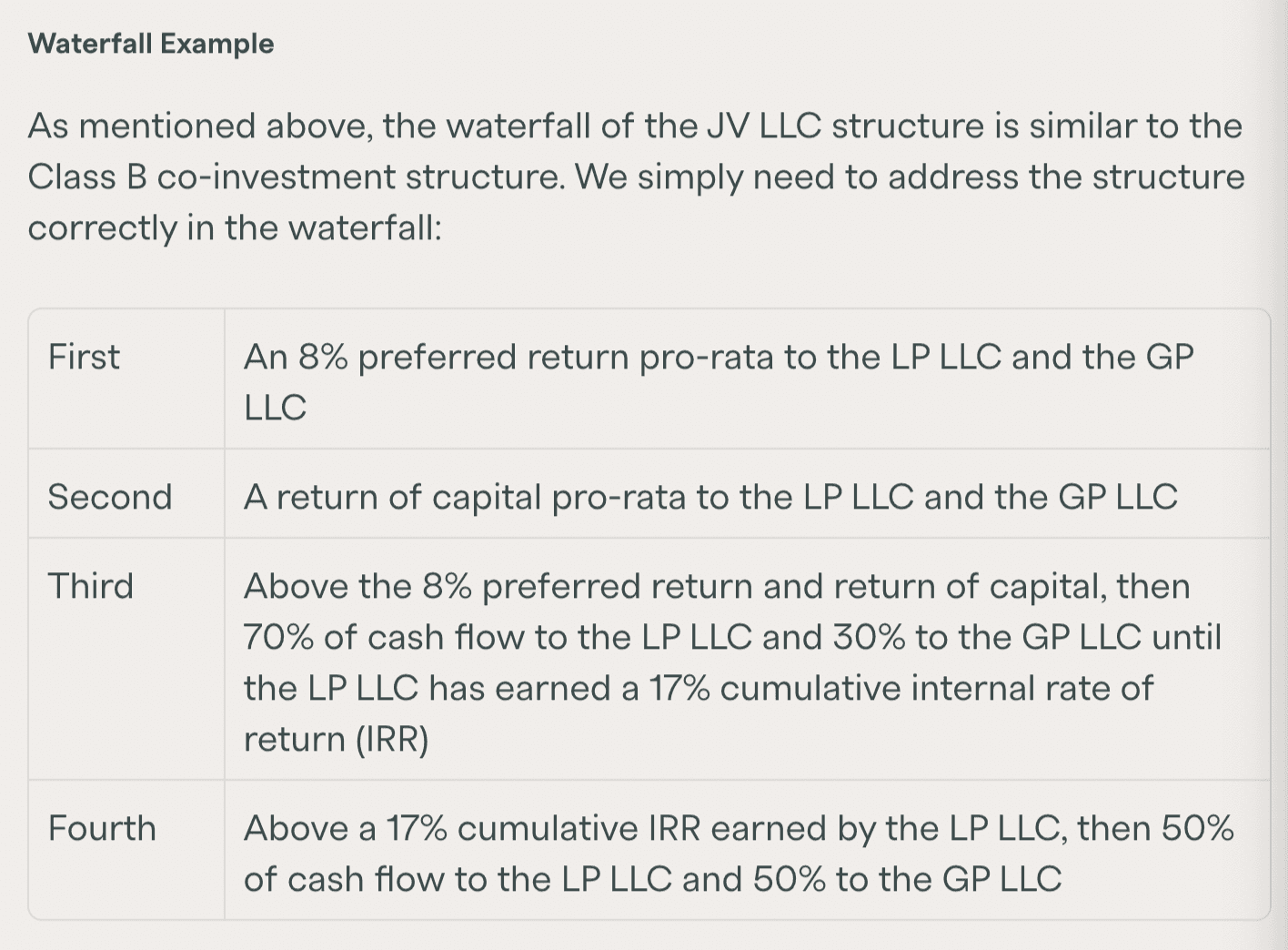

The final structure discussed in this article is the JV LLC. From a cash-flow standpoint, it is nearly identical to the Class B co-investment structure, but with a few key differences:

The structure uses three LLCs, with the JV LLC holding title to the property.

The GP and LP each join the JV LLC through their own separate LLCs, giving LPs their own standalone entity.

Control provisions between the GP and LP are defined in the JV LLC Agreement. There are no Class A or Class B Members in this setup.

The JV LLC is a more formal framework that keeps the GP and LP in separate entities rather than combining them as members of a single LLC. In a single-entity structure, the Manager has significant authority. If an LP wants more influence over the deal — and does not want the GP to serve as the Manager of the controlling entity — the JV LLC structure is generally considered more suitable.

For this reason, we’ve observed that JV LLC structures are common when an operator partners with an institutional LP. Institutional investors are generally comfortable giving the GP day-to-day operational authority, but they are not always willing to grant sole discretion over major decisions, such as when to sell the asset or whether the entity can initiate bankruptcy. The JV LLC format provides a clearer framework for shared control, whereas a single-LLC structure typically grants the GP broader powers, with major decisions handled either at the GP’s discretion or through a vote of all equity partners.

Tips to Remember:

In true promote structures, the sponsor’s equity is part of “all equity.” The waterfall will show equal treatment up to a hurdle, followed by promote tiers.

When the sponsor contributes capital through a separate class, waterfalls describe cash-flow splits, not pure promotes. Investors must back out the sponsor’s pro-rata equity to determine the actual promote.

JV LLCs work like the separate-class structure but provide more formal governance, with GP and LP capital housed in distinct entities.

The Key Takeaway

The distinction between cash-flow splits and true promotes is a common source of confusion for individual investors. Sponsors generally outline these structures clearly, but assumptions about investor familiarity can lead to misunderstandings. By understanding how each structure handles the sponsor’s co-investment, investors can identify the true promote in any of the three scenarios.

Crowd Street always references the true promote — the percentage of profits the sponsor receives above each hurdle. When an offering uses a cash-flow split rather than a pure promote structure, the Marketplace will show both the stated split (e.g., 60/40) and the true promote percentage (e.g., 70/30 assuming a ten percent sponsor co-invest).